Gentile Da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi, 1423, Tempera on Panel - Strozzi Family.

Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi, 1423, tempera on panel, 283 x 300 cm (Uffizi Gallery, Florence) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

After Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea, during the time of Male monarch Herod, Magi from the east came to Jerusalem two and asked, "Where is the 1 who has been born king of the Jews? Nosotros saw his star when it rose and take come to worship him." […] 10 When they saw the star, they were charmed. 11 On coming to the business firm, they saw the kid with his female parent Mary, and they bowed down and worshiped him. Then they opened their treasures and presented him with gifts of aureate, frankincense and myrrh.Matthew 2:1-2, 10-11, NIV

The journey of the wise men

Bright gilt brocades. Psuedo-Arabic. Turbans. Leopards and lions. Gentile da Fabriano'due south Adoration of the Magi creates a dynamic visual narrative of the journey of the Magi to Bethlehem recounted in the Gospel of Matthew. The painting uses continuous narrative to show us the moment the Magi start run across the star announcing Jesus' birth, their journey to Jerusalem, and then subsequent arrival in Bethlehem where they meet the infant Jesus. Three gilded arches (forming part of the elaborate frame) differentiate the three narrative moments, although the final moment—when they get in at the cave in Bethlehem where Mary, Joseph, and Jesus residual—spills across the foreground.

Hither the Magi take turns kneeling before Jesus and presenting him with gifts (of gilt, frankincense, and myrrh). In Gentile's painting, the oldest Magi (eventually known equally Melchior) is kissing Jesus' foot, as the Christian messiah (Jesus) touches his head. The other ii Magi (Caspar, heart aged; and Balthazar, immature) prepare to practice the same, property their gifts aloft. All three Magi are elaborately dressed, and each one has a golden crown.

Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi (item with the Virgin Mary in blue, Joseph in yellow backside her, Jesus on her lap beingness kissed past the king Melchior, with kings Casper stooping, and Balthazar continuing), 1423, tempera on console, 283 10 300 cm (Uffizi Gallery, Florence, photo: Steven Zucker, CC By-NC-SA 4.0)

The Magi were thought to be from east of Europe (though the specific origins of each Magi are not noted in the Bible). By the later Middle Ages, the Magi were understood equally standing in for the world, with each of them coming from Asia, Africa, and even Europe. By the fifteenth century, when Gentile was working, this image of a more than globalized array of Magi had been widely adopted. It provided a lavish sense of different places, and allowed artists to show a variety of exotic luxury goods. It also helped to give the impression of a united world under God.

Interior of Santa Trinità, Florence (photo: Steven Zucker, CC Past-NC-SA 4.0)

Commissioned by Palla Strozzi, a wealthy banker and merchant, for his family unit'south chapel for the Florentine church of Santa Trinità, the Adoration of the Magi speaks to the global catamenia of goods at this fourth dimension, visual transculturation, too equally the European conceptualization of non-European places and peoples.

Psuedo-Arabic

The haloes around the Madonna and Joseph are a bright gold, emphasizing their holiness. If we await closely at them, we notice the haloes also include what appears to exist writing. This script is actually psuedo-Arabic—a script that approximates Arabic writing, simply is not entirely right. Information technology suggests that the artist could not actually read Arabic; that said, he does include Arabic words also. The haloes as well include decorative rosettes separating each word. Psuedo-Standard arabic script doesn't simply announced on Mary's and Joseph'southward haloes either. The immature page, standing next to the white horse in the foreground, wears a sash written in the script. Ane of the female figures behind Mary, whose back is turned to us, wears a white shawl decorated with pseudo-Arabic writing. The sleeves of the youngest Magi suggest the script as well, written at the elbow. Here Gentile seems to write the discussion al-'ādilī (The Just).[1]

Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi (detail with psuedo-Standard arabic script seen in Mary'southward halo and cloth at left), 1423, tempera on panel, 283 x 300 cm (Uffizi Gallery, Florence, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

But why would the artist include psuedo-Arabic in one of the holiest scenes from the life of Jesus? One possible reason is that other Italian artists similarly included psuedo-Arabic into their paintings—often on haloes or textiles—and Gentile was continuing this tradition. We detect examples in the paintings of Duccio, Giotto, and Masaccio, and in sculptures similar Verocchio's David and Filarete's doors for the Vatican. Gentile incorporated pseudo-Standard arabic into other paintings, such as his Madonna of the Humility (c. 1420) and Coronation of the Virgin (c.1420). Information technology is probable more complicated than Gentile solely copying other artists notwithstanding.

Bowl (Mamluk, Syria), 14th century, contumely, incised and engraved, with traces of silver inlay, 7.62 x 16.51 cm (LACMA)

Information technology seems that artists like Gentile borrowed motifs and stylistic patterns from Ayyubid or Mamluk metalwork and textiles that they encountered first hand. These were highly coveted luxury objects and materials, and wealthy families—like the Strozzi—ofttimes owned examples. The city of Florence also had made several diplomatic missions to important Muslim merchandise areas, including one in 1421 to Tunis and another in 1422–23 to Cairo. They established a commercial treaty with the Mamluk sultan in Egypt, and opened a directly trade route to Alexandria via Pisa (which Florence captured in 1406) and Livorno (controlled by Florence after 1421). Information technology has been suggested that these commercial ties may have stimulated fifty-fifty greater involvement in luxury objects, like Mamluk brass objects, and the decorative schema institute on them.

A 3rd possible reason is that pseudo-Arabic connoted sacredness in some way. The metropolis of Jerusalem (and the Holy Lands more than mostly) is in the eastern Mediterranean and in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries these areas were controlled by Muslim rulers. Perhaps the use of Arabic script was a way for artists like Giotto and Gentile da Fabriano to reference the Holy Lands within their paintings, or even to suggest the common heritage of Islam and Christianity.

Gentile da Fabriano, Admiration of the Magi (detail), 1423, tempera on panel, 283 x 300 cm (Uffizi Gallery, Florence, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Wearing signs of "the e"

Also the employ of psuedo-Arabic, other elements of the painting point to Gentile's desire to call to mind "the eastward" and the exotic sense of the Holy Lands. Multiple figures in the painting wear turbans, a common visual sign that indicated someone from outside Christian Europe, typically someone of Centre Eastern descent. Caspar, the second Magi, wears one. They are used here to suggest the Holy Lands again, also every bit the eastern or non-European origins of some of the Magi. Afterward all, the journeying of the Magi takes them to Jerusalem and onto Bethlehem, and so the turban here communicates that the scene is exterior of Christian territory, in a more than exotic location.

Besides turbans, we also detect figures, such as the Magi, wearing elaborate brocades, damasks, other silks, and velvets. Melchior wears a patterned garment of pearlescent white with golden accents, and to a higher place that a mantle of burnt siena absolute with gold and silver. On both, rosettes and other floral designs animate the surface. Caspar wears a long tunic in blackness busy with golden pomegranates.

While the pomegranate was a prominent Christian symbol of rebirth, it was too mutual as a symbol of its eastern origins and information technology was a popular motif in Muslim textiles equally well. Gentile also includes pomegranate copse in the painting to connote Jerusalem'southward and Bethlehem's eastern locales. Balthazar's outfit is similarly elaborate. His abdomen is covered in gold designs that well-nigh mimic peacock feathers. His long and elaborate sleeves extend to his knees, and are enlivened by reddish flowers scrolling beyond the surface. Golden and silver fringe can be found on the edges of his entire outfit.

The exact origins of these textiles is difficult to pinpoint but they all evoke "eastern" patterns and textiles. They could have been acquired by trade from Muslim merchants, or produced in Italia. Cities like Venice, Genoa, and Florence became skilled centers of silk product, and their designs often mimic Muslim textile patterns. Such wearable (whether acquired from afar or made in Italy), was expensive, and was highly sought after by elites. The ornate advent of the Magi's clothes in Gentile's painting does seem to advise that they are men "from the east."

Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi (item with page in the center and a leopard or cheetah in upper right. Annotation the utilize of pastiglia seen especially in the tack), 1423, tempera on panel, 283 ten 300 cm (Uffizi Gallery, Florence, photo: Steven Zucker, CC By-NC-SA 4.0)

An exotic menagerie

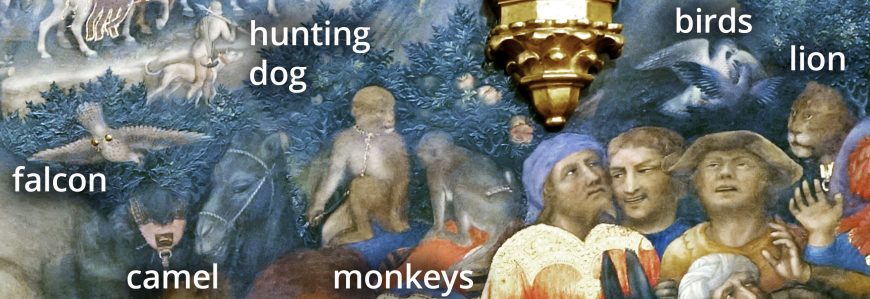

As if the painting wasn't already a feast for the optics, Gentile has also included a number of non-European or exotic animals into the riotous scene. Two monkeys sit atop a camel. We too detect a lion eyeing two birds, and further below a leopard (or possible cheetah) amidst the tightly packed group of men. Animals from outside Europe (Asia, Africa, and eventually the Americas after 1492) were a constant source of interest for Europeans. They were nerveless, given as gifts, and sometimes even trained to join in ladylike hunting expeditions.

Falcons were not necessarily an exotic predatory bird, but falconry had been heavily influenced past Arabian/Muslim traditions. Falcons were especially associated with Western farsi civilisation. New falcons caused from afar lands as well appealed to Italian elites. The man property the falcon is possible a member of the Strozzi family (possibly Palla, the patron) because the Italian word for falconer is strozziere.

Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi (detail with animals), 1423, tempera on panel, 283 10 300 cm (Uffizi Gallery, Florence, photo: Steven Zucker, CC By-NC-SA 4.0)

Wealthy individuals sometimes acquired exotic animals as a sign of their wealth and their interest in the natural world. Monkeys and apes were popular collectibles, and here they wear collars and then as non to escape. Large cats, like the leopard and lion, were sometimes kept and trained for hunting, especially among the northern Italian courts. Exotic animals like camels were pop gifts.

The non-European animals in the painting also assist to fix the scene in a more exoticized eastern location. The horses are probable Arabian horses, acquired from Muslim trading partners. The camel's associations with the Holy Lands are mentioned in the Bible. While at that place is no peacock displayed in the painting, ane man does article of clothing a hat/headdress fabricated of its feathers. The peacock, every bit a symbol of resurrection, dated back to antiquity. Peafowl came from Asia, namely India, and the man'due south headgear helps to further associate his eastern origins.

And of grade, some of these exotic animals had symbolic meaning that played a role in the painting. Matthew 19:24 famously notes that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven. Hither, it might symbolically remind wealthy viewers, like the Strozzi, of this alarm.

Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi (detail with Jesus and Melchior), 1423, tempera on panel, 283 x 300 cm (Uffizi Gallery, Florence, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA iv.0)

Material brilliance

The 2 well-nigh expensive materials used in this painting are lapis lazuli and aureate. The Virgin Mary's robe is ultramarine, or a brilliant blue color derived from lapis lazuli. It came from mines in Transitional islamic state of afghanistan. It could only be mined five months out of the twelvemonth likewise, increasing its monetary worth. At this time in the Renaissance, information technology was more valuable than gilded. This is why artists like Gentile often reserved it for Mary's mantle, using other blue pigments throughout the residue of the painting.

Golden was also expensive, and Gentile has used a lot of it hither. Palla Strozzi, wanting to annunciate his wealth, would surely have been thrilled by the lavish use of the gold across the surface. Most gold came from west Africa, traded forth caravan routes. Republic of mali, which at one point had been ruled by the powerful and wealthy Musa Keita I (known as Mansa Musa in Europe) reputedly had an enormous amount of aureate. When Musa Keita I traveled to Mecca on the hajj between 1324 and 1325 he flooded the market with gold and acquired an economic collapse considering the cost of aureate fell steeply.

Gentile doesn't just incorporate gold into his painting, he uses a technique to suggest an even greater abundance of the precious metal. He uses pastiglia, or raised gilt decoration, which we run across on the crowns, swords, spurs, and even on some textiles. It gives these golden areas a iii-dimensional quality because they are raised from the flat surface of the painting. Imagine the shimmering quality of all this gilt and other fabric magnificence in the flickering candlelight of the Strozzi chapel!

[i] Ennio G. Napolitano, Arabic Inscriptions and Pseudo-Inscriptions in Italian Fine art (PhD dissertation, Otto-Friedrich-Universität, Bamberg), p. 99.

Additional resources

Learn more about the expanding the renaissance initiative

Anna Contadini, "Sharing a Taste? Fabric Culture and Intellectual Marvel effectually the Mediterranean, from the Eleventh to the Sixteenth Century," in The Renaissance and Ottoman World, ed. Anna Contadini and Claire Norton (London: Ashgate, 2013), 24–61.

Maria Vittoria Fontana, "The influence of Islamic fine art in Italy," Annali dell'Università degli studi di Napoli "L'Orientale," Rivista del Dipartimento di Studi Asiatici eastward del Dipartimento di Studi east Ricerche su Africa e Paesi Arabi, vol. 55,no. 3 (1995).

Rosamund Due east. Mack, Boutique to Piazza: Islamic Trade and Italian art, 1300–1600 (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002).

Alexander Nagel, "Twenty-v notes on pseudoscript in Italian art," RES: Journal of Anthropology and Aesthetics, vol. 59/sixty (Leap/Autumn 2011), pp. 229–248.

Patricia Lee Rubin, Images and Identity in Fifteenth-century Florence (New Haven and London:Yale University Press, 2007).

Source: https://smarthistory.org/gentile-da-fabriano-adoration-magi-reframed/

0 Response to "Gentile Da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi, 1423, Tempera on Panel - Strozzi Family."

Post a Comment